overstriding and forefoot striking… read more

If you are still not convinced that changing the way you are running will stop your injury rate…. here is some light reading to convince you. Different areas of the body are referenced below. All areas of the body need to be addressed if you want to create the perfect running gait. It can be changed, it takes time and coaching, but makes a massive difference.

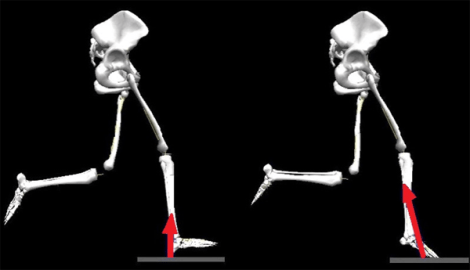

Overstriding / Impact Forces

Overstriding is linked to excessive impact forces and patellofemoral joint stress

Lenhart RL, Wille CM, Chumanov ES, et al. Kinematic and kinetic predictors of patellofemoral joint force in healthy runners. Presented at the 60th Annual Meeting of the American College of Sports Medicine, Indianapolis, May 2013.

Edwards WB, Taylor D, Rudolphi TJ, et al. Effects of stride length and running mileage on a probabilistic stress fracture model. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2009;41(12):2177-2184.

Impact Forces contributes to tibial stress and PFP.

Pohl MB, Mullineaux DR, Milner CE, et al. Biomechanical predictors of retrospective tibial stress fractures in runners. J Biomech 2008;41(6):1160-1165

Milner CE, Ferber R, Pollard CD, et al. Biomechanical factors associated with tibial stress fracture in female runners. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2006;38(2):323-328

Davis I, Bowser, B, Mullineau, D. Do impacts cause running injuries?A prospective investigation. Presented at the American Society of Biomechanics Annual Meeting, Providence, RI, August 2010

Anterior Shins Splints: Contributing factors can be linked to foot inclination angle at initial contact (i.e. landing heel-to-toe with high toe), can be linked to overstride (i.e. vertical tibial angle at footstrike) and indirectly linked to slow cadence (via overstride)

Franklyn-Miller, Andrew, et al. “Biomechanical overload syndrome: defining a new diagnosis.” British journal of sports medicine 48.6 (2014): 415-416.

A optimal cadence can significantly reduce overstride, braking impulse, peak vertical ground reaction force, foot inclination angle at initial contact, and energy absorbed at the knee during loading response.

Heiderscheit BC, Chumanov ES, Michalski MP, et al. Effects of step rate manipulation on joint mechanics during running. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2011;43(2):296-302

Cross Over / Step Width / Hip Adduction / Medial Collapse

Excessive cross over (hip adduction) and hip internal rotation result increase the dynamic Q angle, increasing the lateral force on the patella.

Powers CM. The influence of abnormal hip mechanics on knee injury: a biomechanical perspective. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2010;40(2):42-51.

Medial collapse of the knee is linked to tibial stress fracture as it increases the bending forces on the tibia and puts tension on the medial tibia

Pohl MB, Mullineaux DR, Milner CE, et al. Biomechanical predictors of retrospective tibial stress fractures in runners. J Biomech 2008;41(6):1160-1165.

Milner CE, Hamill J, Davis IS. Distinct hip and rearfoot kinematics in female runners with a history of tibial stress fracture. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2010;40(2):59-66.

Cross-over: There is a greater ITB strain strain rate associated with narrower step width. Decreasing step with by a very small amount substantially increases ITB strain. On the other hand. Running with the feet 3cm wider reduced ITB tension by up to 20%.

Meardon, Stacey A., Samuel Campbell, and Timothy R. Derrick. “Step width alters iliotibial band strain during running.” Sports Biomechanics 11.4 (2012): 464-472.

Activation of hip abductors, extensor and external rotators is related to the body’s ability to control frontal and transverse plane motion at the knee

Mascal, Catherine L., Robert Landel, and Christopher Powers. “Management of patellofemoral pain targeting hip, pelvis, and trunk muscle function: 2 case reports.” Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy 33.11 (2003): 647-660.

Medial collapse (excessive hip drop, hip adduction, and hip internal rotation) is a potential contributor to tibial stress fractures, PFP, and ITB syndrome in runners.

Pohl MB, Mullineaux DR, Milner CE, et al. Biomechanical predictors of retrospective tibial stress fractures in runners. J Biomech 2008;41(6):1160-1165.

Willson JD, Davis IS. Lower extremity mechanics of females with and without patellofemoral pain across activities with progressively greater task demands. Clin Biomech 2008;23(2):203-211.

Noehren B, Davis I, Hamill J. ASB clinical biomechanics award winner 2006 prospective study of the biomechanical factors associated with iliotibial band syndrome. Clin Biomech 2007;22(9):951-956.

Milner CE, Ferber R, Pollard CD, et al. Biomechanical factors associated with tibial stress fracture in female runners. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2006;38(2):323-328.

Souza RB, Powers CM. Differences in hip kinematics, muscle strength, and muscle activation between subjects with and without patellofemoral pain. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2009; 9(1):12-19.

Greater hip adduction and internal rotation excursion was correlated with later gluteus medius and gluteus maximus onset, respectively.

Willson, John D., et al. “Gluteal muscle activation during running in females with and without patellofemoral pain syndrome.” Clinical biomechanics 26.7 (2011): 735-740.

Cadence

Patellofemoral joint stress decreases when cadence is increased.

Lenhart RL, Wille CM, Chumanov ES, et al. Kinematic and kinetic predictors of patellofemoral joint force in healthy runners. Presented at the 60th Annual Meeting of the American College of Sports Medicine, Indianapolis, May 2013

A optimal cadence can significantly reduce overstride, braking impulse, peak vertical ground reaction force, foot inclination angle at initial contact, and energy absorbed at the knee during loading response.

Heiderscheit BC, Chumanov ES, Michalski MP, et al. Effects of step rate manipulation on joint mechanics during running. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2011;43(2):296-302

Optimal stride frequency is on average 3% faster than a runner’s preferred frequency

Moore, Isabel S. “Is There an Economical Running Technique? A Review of Modifiable Biomechanical Factors Affecting Running Economy.” Sports Medicine (2016): 1-15.

Increasing cadence results in decreases in stride length, hip adduction angle and hip abductor moment.

Hafer, Jocelyn F., et al. “The effect of a cadence retraining protocol on running biomechanics and efficiency: a pilot study.” Journal of sports sciences 33.7 (2015): 724-731.

Foot / Calf / Achilles

Excessive plantar flexion with overstride and link to Achilles and calf strain

Lieberman, Daniel E. “What We Can Learn About Running from Barefoot Running: An Evolutionary Medical Perspective”. Exercise and Sport Sciences Reviews, Publish Ahead of Print (2012).

Link between cadence, overstride, Centre of Mass, braking impulse, peak vertical ground reaction force, foot inclination angle at initial contact, and energy absorbed at the knee during loading response.

Heiderscheit BC, Chumanov ES, Michalski MP, et al. Effects of step rate manipulation on joint mechanics during running. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2011;43(2):296-302

Heel strike angle linked with vertical ground reaction forces

Lieberman, Daniel E. “What We Can Learn About Running from Barefoot Running: An Evolutionary Medical Perspective”. Exercise and Sport Sciences Reviews, Publish Ahead of Print (2012).

Dysfunction of musculature of the lumbopelvic–hip complex is involved in lower extremity functional changes and is related to the development some pathologies traditionally attributed to excessive foot pronation

Barwick, Alex, Josephine Smith, and Vivienne Chuter. “The relationship between foot motion and lumbopelvic–hip function: A review of the literature.” The Foot 22.3 (2012): 224-231.

- During normal running gait, it is understood that GMED typically activates before heel strike, with continued activation through early stance to stabilize the hip and maintain a level pelvis. Before heel strike, individuals with Achilles tendinopathy had delayed onset of GMED.

- Specifically, an altered GMED activation pattern, such as that observed in this study (delayed onset and shorter duration), may result in excessive hip adduction and/or internal rotation. In accordance with the kinetic chain theory, this would translate to internal tibial rotation and, subsequently, greater eversion of the rearfoot.

- it is plausible that different mechanics in runners with Achilles tendinopathy may originate from altered activation of the GMED muscle.

- It is plausible that an altered GMAX activation pattern, such as that observed in this study (delayed onset, earlier offset, and shorter duration), could result in GMAX not sufficiently controlling femoral position in preparation for heel strike and during stance phase.

- altered GMAX activation may influence femoral adduction and/or internal rotation and, in turn, foot pronation.

- GMAX is the primary hip extensor during gait, and differences in its activation, as shown in this study, will likely have significant ramifications for lower limb motor control during running. It is possible that a shorter duration of GMAX activation may result in reduced hip extensor power and forward propulsion of the center of mass.

- it is conceivable that a shorter duration of GMAX activation may reflect or cause an increased contribution toward forward propulsion from the ankle joint. This increased contribution from the ankle joint may be achieved by increased concentric triceps surae activation and, consequently, greater concentric load on the Achilles tendon.

- It is possible that the presence of pain in the Achilles tendon may have altered the activation patterns of the GMED and GMAX during the running task.

Smith, Melinda M., et al. “Neuromotor control of gluteal muscles in runners with achilles tendinopathy.” Med Sci Sports Exerc 46.3 (2014): 594-599.

No difference in running economy between rearfoot and forefoot striking at slow, medium and fast speeds. In some cases, rearfoot is more economical than midfoot at slow running speeds. Habitual forefoot strikers can change to a rearfoot strike without detrimental consequences to RE, while an imposed forefoot strike in habitual rearfoot strikers produces worse RE at slow and medium speeds.

Moore, Isabel S. “Is There an Economical Running Technique? A Review of Modifiable Biomechanical Factors Affecting Running Economy.” Sports Medicine (2016): 1-15.

Pelvis / Trunk / Glute Activation

- Glute Max tend to contract bi-phasically with a first burst just prior to heel strike in the ipsilateral side, and a second, shorter burst prior to mid swing about the time of the heel strike on the contralateral side – pg 2147

- Glute max becomes more involved at higher velocity (at very high speeds the magnitude and duration of activity increases for both burst blurring the distinction between these bursts in so minds) – pg 2147

- Glute max may help to prevent the hip from collapsing into flexion during stance phase

- Small amounts of GM activity may contribute to hip extension during stance, and restraint to hip flexion during swing.

- The GM functional largely as a trunk stabilizer during running

- The most likely function swing-side contractions of the GM is to decelerate the leg during the swing phase

Lieberman, Daniel E., et al. “The human gluteus maximus and its role in running.” Journal of Experimental Biology 209.11 (2006): 2143-2155.

- Improving performance of the hip abductors would result in a more optimal alignment of the pelvis during single-limb activities and, in turn, protect the knee joint from excessive frontal plane moments created by compensatory adjustments of the trunk and the resulting movement of the body center of mass.

- With respect to the sagittal plane, excessive anterior tilting of the pelvis resulting from weakness of the posterior rotators of the pelvis (ie, gluteus maximus, hamstrings, and abdominals) and/or tightness of the hip flexors may result in compensatory lumbar lordosis and a resulting posterior shift in the trunk position. As described earlier, a posterior shift in the center of mass during functional activities would increase the knee flexion moment and the demand on the knee extensors, while simultaneously decreasing the hip flexion moment and the demand on the hip extensors. In such a scenario, the compensatory posterior shift of the trunk and center of mass may perpetuate hip extensor weakness and, in turn, result in greater anterior tilting of the pelvis. This chain of events may explain the clinical observations of hip extensor weakness in persons who present with excessive anterior tilt of the pelvis.

- dynamic trunk stability cannot exist without pelvis stability. Although the trunk musculature (ie, abdominals, transverse abdominis, obliques, multifidi, erector spinae) plays an important role in stabilizing the spine, these muscles would not be expected to prevent compensatory trunk motions associated with poor pelvis control. Given the fact that impaired trunk proprioception and deficits in trunk control have been shown to be predictors of knee injury, 85,86 the development of “core” programs should consider dynamic pelvis stability as an integral aspect of the training protocol.

- As a single joint muscle, the gluteus maximus is best suited to provide 3-dimensional stability of the hip, as this muscle resists the motions of hip flexion, adduction, and internal rotation.52 In contrast, the gluteus medius mainly functions to stabilize the femur and pelvis in the frontal plane.52 Although the posterior fibers of the gluteus medius can assist in hip extension and external rotation, the overall contribution to these motions is modest at best.52

- Apart from being a strong hip extensor, the gluteus maximus is the most powerful external rotator of the hip.52 Its external rotation capacity is supplemented by the actions of the deep hip rotators (ie, piriformis) and the posterior fibers of the gluteus medius. Furthermore, the upper portion of the gluteus maximus has the ability to abduct the hip and demonstrates an activation pattern similar to that of the gluteus medius.41 Thus, the frontal and transverse plane control afforded by the gluteus maximus suggests that this muscle is well suited to protect the knee from proximal movement dysfunction. Lastly, the data of Pollard and colleagues57 suggest that improving use of the gluteus maximus in the sagittal plane may serve to “unload” the knee by decreasing the need for compensatory quadriceps action to absorb impact forces.

- The ability of the gluteus maximus and gluteus medius to provide dynamic stability of the hip and pelvis may be influenced by the biomechanics of the task being performed. For example, Ward and colleagues78 have reported that during weight bearing, the ability of the gluteus maximus and gluteus medius to generate torque decreases with increasing hip flexion. The reduction in torque generation with hip flexion can be attributed to both mechanical and physiological factors (ie, diminished leverage and less optimum muscle length-tension characteristics, respectively).

Powers, Christopher M. “The influence of abnormal hip mechanics on knee injury: a biomechanical perspective.” journal of orthopaedic & sports physical therapy 40.2 (2010): 42-51.

Abnormal or excessive force on the anterior hip joint may cause anterior hip pain, subtle hip instability and a tear of the acetabular labrum. We found that decreased force contribution from the gluteal muscles during hip extension and the iliopsoas muscle during hip flexion resulted in an increase in the anterior hip joint force. The anterior hip joint force was greater when the hip was in extension than when the hip was in flexion.

Lewis, Cara L., Shirley A. Sahrmann, and Daniel W. Moran. “Anterior hip joint force increases with hip extension, decreased gluteal force, or decreased iliopsoas force.” Journal of biomechanics 40.16 (2007): 3725-3731.

ARM RESEARCH

Not using arms requires 12% more metabolic energy. Vertical ground reaction increased by 63% without arm swing.

Collins, Steven H., Peter G. Adamczyk, and Arthur D. Kuo. “Dynamic arm swinging in human walking.” Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences (2009): rspb20090664.

When arm swing was eliminated, the rate of O2 consumption was 8% greater than running with normal arm swing. Efficient arm swing can minimize metabolic cost and optimize for lateral balance

Arellano, Christopher J., and Rodger Kram. “The effects of step width and arm swing on energetic cost and lateral balance during running.” Journal of biomechanics 44.7 (2011): 1291-1295.

The arms were found to reduce the horizontal excursions of the body CM both front to back and side to side, thus tending to make a runner’s horizontal velocity more constant

Hinrichs, Richard N., Peter R. Cavanagh, and Keith R. Williams. “Upper Extremity Function in Running. I: Center of Mass and Propulsion Considerations.” International Journal of Sport Biomechanics 3.3 (1987).

There is no apparent advantage of the “classic” style of swinging the arms directly forward and backward over the style that most distance runners adopt of letting the arms cross over slightly in front. The crossover, in fact, helps reduce side-to-side excursions of the body CM mentioned above, hence promoting a more constant horizontal velocity.

Hinrichs, Richard N., Peter R. Cavanagh, and Keith R. Williams. “Upper Extremity Function in Running. I: Center of Mass and Propulsion Considerations.” International Journal of Sport Biomechanics 3.3 (1987).

Cross-Lateral Coordination: Mature locomotion in humans is characterized by an anti-phase coordination (moving in opposite directions) between the pelvic and the scapular girdles. This pattern involves a specific relationship between the arm and leg motion is deemed to be most flexible and dynamically efficient. Results show that an absence of arm swing led to a change from an anti-phase to in-phase pattern (girdles moving in the same direction) and that an increase in velocity strengthened the adopted pattern.

Dedieu, Philippe, and Pier-Giorgio Zanone. “Effects of gait pattern and arm swing on intergirdle coordination.” Human movement science 31.3 (2012): 660-671.

Swinging the arms during running plays an important role as it contributes to vertical; counters vertical angular momentum of the lower limbs; and minimizes head, shoulder, and torso rotation. Eliminating arm swing can be detrimental to Runny Ecomony . Suppressing arm swing can alter several lower limb biomechanics and kinetics. For example, restraining the arms behind the back and across the chest decreases peak vertical force, increases peak hip and knee flexion angles during stance, and reduces knee adduction during stance. Arm motion plays an integral role in an individual’s running technique.

Cueing & Coaching

Importance of cueing runners to land lightly with appropriate cadence: cueing a 10% increase in step rate resulted in greater preparatory gluteal activity just prior to foot strike, which likely improves control of frontal plane hip mechanics

Chumanov ES, Wille CM, Michalski MP, Heiderscheit BC. Changes in muscle activation patterns when running step rate is increased. Gait Posture 2012;36(2):231-235.

Runners are able to adjust their technique to reduce the mechanical cost of running using visual and auditory feedback.

Eriksson, Martin, Kjartan A. Halvorsen, and Lennart Gullstrand. “Immediate effect of visual and auditory feedback to control the running mechanics of well-trained athletes.” Journal of sports sciences 29.3 (2011): 253-262.

Verbal and visual feedback are effective means of eliciting modifications in running style in female novice runners.

Messier, Stephen P., and Kathleen J. Cirillo. “Effects of a verbal and visual feedback system on running technique, perceived exertion and running economy in female novice runners.” Journal of Sports Sciences 7.2 (1989): 113-126.

There is significant correlations between Running Economy and biomechanical variables (vertical oscillation of the center of mass, stride frequency, stride length, balance time, relative stride length, range of elbow motion, internal knee, ankle angles at foot strike, and electromyographic activity of the semitendinosus and rectus femoris muscles). Changes in running technique can influence RE and lead to improved running performance.

Tartaruga, Marcus Peikriszwili, et al. “The relationship between running economy and biomechanical variables in distance runners.” Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport 83.3 (2012): 367-375.

Mirror gait retraining is effective in improving mechanics and measures of pain and function.

Willy, Richard W., John P. Scholz, and Irene S. Davis. “Mirror gait retraining for the treatment of patellofemoral pain in female runners.” Clinical Biomechanics 27.10 (2012): 1045-1051.

Gait retraining to improve dynamic knee alignment resulted in significant reductions in the knee adduction moment, primarily through hip internal rotation.

Barrios, Joaquin A., Kay M. Crossley, and Irene S. Davis. “Gait retraining to reduce the knee adduction moment through real-time visual feedback of dynamic knee alignment.” Journal of biomechanics 43.11 (2010): 2208-2213.